Humans, Housing and Home

December 2023

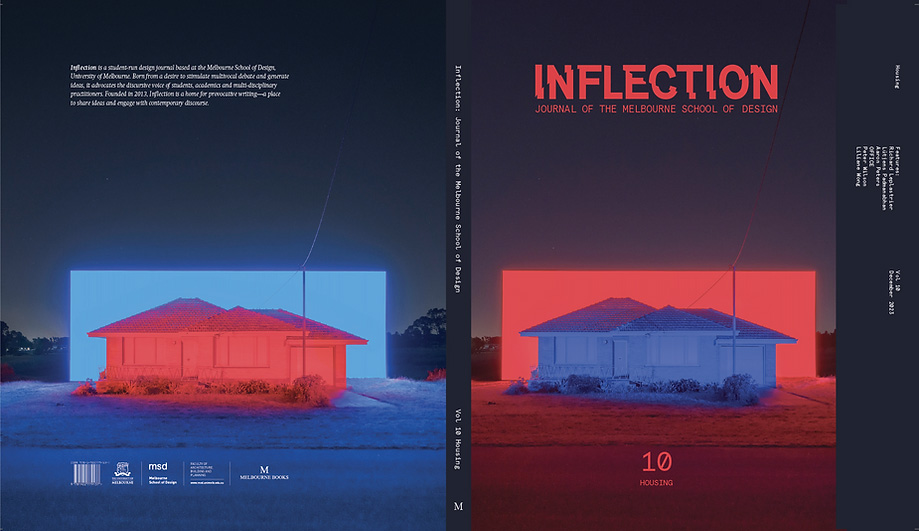

First published in: Inflection - Journal of the Melbourne School of Design

Words by Aaron Peters

December 2023

First published in: Inflection - Journal of the Melbourne School of Design

Words by Aaron Peters

To me, the term 'housing' feels like it belongs to the realm of policy and statistical data. It almost sounds euphemistic, taking an emotionally charged undertaking (building a home) and transmuting it into something cold, distant and dispassionate (delivering housing). Still, here we are amid an affordability and homelessness crisis. Without reform, generations of Australians will likely be priced out of the 'Australian Dream' or trapped in a cycle of housing insecurity. When faced with such urgent problems, there is an understandable tendency to focus on the big picture, sweeping changes that can resolve systemic issues within our socio-political framework¹

. However, without wishing to diminish or distract from the importance of those efforts, this essay will consider housing from a different perspective, one more attuned to the situation encountered by many practitioners charged with delivering the buildings people will be asked to live in. I'm interested in substituting the term 'housing' for 'home'.

When we envisage a home, I think it's fair to assume that we all aspire to live in well-designed places, though it's often difficult to pinpoint what each individual might mean by this. Recently, I was reflecting on the term 'good design' while convalescing after a Covid infection (clearly, I'd run out of Netflix). I started asking myself how it manifests in the day-to-day experience of inhabiting my home and neighbourhood. I thought of fragmentary moments, atmospheres and daily rituals.

I like my house because it feels comfortable and slightly shabby. I like that a striped marsh frog lives in the little pond we installed in the backyard, and I occasionally see it sitting there. I like that many houses in our neighbourhood, including mine, still display visible signs of life on the street. I like that the share-house two doors up hosts parties on the grass in their backyard. I like sitting on the top step to put on my shoes and chatting with neighbours as they pass by. I like walking to my son's school, the office, and the local shops. I would like it more if shade trees were permitted to grow larger and were not hacked to pieces when they interfere with the overhead wires.

One of the nicest streets in the neighbourhood is a narrow residential street where two or three of the houses have given over their front yards to allow the pedestrian verge to widen. There's a tyre swing, a bench, a small productive garden and a mulberry tree that families with young kids regularly ransack.

These small-scale architectural and urban gestures directly impact the quality of my life, yet they rarely figure in 'serious' professional discourse. We often design at the urban scale by considering the mass movement of traffic, generic building form, height and massing, reductive designations of use and occupation like 'zoning', and provision of critical servicing infrastructure. These considerations are essential, of course, but I began to wonder, what if we were to start by considering urban design at a more intimate scale: the scale of a room, an event involving just one or a handful of people, or an architectural element, like a window? Could this approach assist with translating my seemingly quaint observations about suburban life into affordable, desirable, higher-density housing models?

As I have tried to illustrate above (albeit obliquely), I believe the distinction between housing and life-enhancing homes is a little dash of humanity. My house was once a low-cost worker's cottage, built over a century ago to provide necessities to a working-class population. Many attributes that make it remarkable and a privilege to live in are not feasible or sustainable to deliver today. We should not allow ourselves to become confused by this. Replicating traditional craft practices or allocating large suburban lots in an era of growing land scarcity is not something we need to try and reproduce to make humane dwellings. Architecture can make a meaningful social contribution by thoughtfully arranging space to enhance everyday events and enable civility within urban settings.

![]()

We can start by situating openings to receive light and air and admit the presence of nature. That's as simple as making observations about the setting of a building and thinking carefully about where a window is placed in a wall. We can design buildings that dampen sound transmission between adjoining dwellings, are energy efficient and treat the ground plane as a resource, not a potential threat. We can take better care of servicing, ensuring that AC condensers, poo-pipes, and refuse collection aren't immediately adjacent to the lift lobby. We can see communal gardens as more than ornamental. We can design buildings capable of incremental change and adaptation that permit occupants to express their individuality and alter their homes and surroundings to suit their evolving requirements within the framework of a larger building ensemble. If we did that, many more people would have the ability to participate in shaping the city. Our cities would be better able to adapt to new circumstances, and we'd be less reliant on private developers to envisage and deliver our collective futures. These things can all manifest in low-cost, medium-to-high-density buildings supported by parkland and public transport.

These things matter to individuals, but they also resonate within communities, which redounds to our collective benefit. Michael Sorkin's memoir Twenty Minutes in Manhattan is an evocative and insightful account of embodied urbanism in one of the world's most famously dense and highly populated urban environments. For Sorkin, stoops, door thresholds, hallways and stairwells are places of social exchange. The door frame is what we lean on as we lend a phone charger, and the stair is a place to negotiate relationships and swap gossip as people go about their lives. Windows are how we situate our inner lives in the context of a wider world, how the life of the city enters our sanctum. As Sorkin observes:

Such direct transactions are foundational for our politics. Translations of the face-to-face into the door-to-door or into the leaflet passed hand-to-hand in the street are crucial steps in a chain of associations that form a binder for civic life and limn the scale of our community, fixing the dimensions of our collective self-interest, the boundaries of "home." 2

If we thought about buildings in this way, as agents of social and political advancement, we might be inclined to deepen a façade to make it occupiable in places, open a lobby to the outdoors, raise a planter bed to seat height, widen a stair, recess an apartment door to accommodate a pot plant, a door mat and a loitering neighbour. It might only take a few centimetres to create the potential for something important to happen.

Despite how we often simulate architectural practice in universities or critique completed buildings in professional discourse, the architect usually has little control over the work they are offered. They don't typically write the brief, set the budget or conjure the ideal site from a mysterious, hidden orifice. Architectural commissions come unexpectedly, with largely fixed parameters and limited scope for negotiation. Those conditions are not always as ideal as we might wish.

Having a good idea or honourable intentions is only part of the challenge. To turn housing into homes, we need to be persuasive. I know of one prominent practitioner who has joked that his principal skill as an architect is to get his client to double their budget before he's put pen to paper. That kind of talent can also be put to many, more worthy, uses.

Persuasion should begin with compassion and listening. It should also include acknowledging stakeholders who do not have a seat at the table and advocating on their behalf. For a profession allied to and infused with privilege, that's a significant challenge requiring effort. Most practice directors, like me, are incredibly fortunate in both the accident of their birth and their life circumstances. Our client base and social circles typically include people with money, power, and education exceeding the average. Engaging directly with stakeholders, participating in the broader community and staying abreast of public discourse concerning social and economic justice seem like sensible responses. Likewise, talking to your client about the commission quickly reveals where stipulations of the brief are founded on scant evidence or demands are arrived at via untested assumptions. I know from experience that the client and the architect can be vulnerable to such oversights.

A healthy degree of uncertainty is an asset for an architect, not a weakness. Architects tend to know a little about many things. We are generalists coordinating the specialised knowledge of the many experts required to deliver a modern building. Under the right circumstances, we can learn from all of them.

Ultimately, the life of a building is enacted by occupants, not architects, and civility consists of everyday gestures, like kind words, not cladding systems. Architecture can prohibit or encourage certain activities, modifying how and when people encounter one another, how they feel about their environment, and how their environment reflects on them and their prospects in life. However, it takes a lifetime of careful study and observation to demystify the intricate reciprocities between buildings and people. Rather than be deterred or intimidated by that prospect, we should embrace it. Life is fascinating, constantly surprising and inspiring.

When we speak about 'housing' or 'good urban design,' we should base our understanding on people, their dreams and aspirations. Amid a housing crisis that compels us to shift our focus to encompass the magnitude of the challenge, we must avoid losing sight of the salient details, including those who will spend their lives in the spaces created. We cannot afford to rehouse generations of Australians whose hastily constructed neighbourhoods fall into decline because, in our urgency to alleviate a housing crisis, we forget that we are housing humans.

When we envisage a home, I think it's fair to assume that we all aspire to live in well-designed places, though it's often difficult to pinpoint what each individual might mean by this. Recently, I was reflecting on the term 'good design' while convalescing after a Covid infection (clearly, I'd run out of Netflix). I started asking myself how it manifests in the day-to-day experience of inhabiting my home and neighbourhood. I thought of fragmentary moments, atmospheres and daily rituals.

I like my house because it feels comfortable and slightly shabby. I like that a striped marsh frog lives in the little pond we installed in the backyard, and I occasionally see it sitting there. I like that many houses in our neighbourhood, including mine, still display visible signs of life on the street. I like that the share-house two doors up hosts parties on the grass in their backyard. I like sitting on the top step to put on my shoes and chatting with neighbours as they pass by. I like walking to my son's school, the office, and the local shops. I would like it more if shade trees were permitted to grow larger and were not hacked to pieces when they interfere with the overhead wires.

One of the nicest streets in the neighbourhood is a narrow residential street where two or three of the houses have given over their front yards to allow the pedestrian verge to widen. There's a tyre swing, a bench, a small productive garden and a mulberry tree that families with young kids regularly ransack.

These small-scale architectural and urban gestures directly impact the quality of my life, yet they rarely figure in 'serious' professional discourse. We often design at the urban scale by considering the mass movement of traffic, generic building form, height and massing, reductive designations of use and occupation like 'zoning', and provision of critical servicing infrastructure. These considerations are essential, of course, but I began to wonder, what if we were to start by considering urban design at a more intimate scale: the scale of a room, an event involving just one or a handful of people, or an architectural element, like a window? Could this approach assist with translating my seemingly quaint observations about suburban life into affordable, desirable, higher-density housing models?

As I have tried to illustrate above (albeit obliquely), I believe the distinction between housing and life-enhancing homes is a little dash of humanity. My house was once a low-cost worker's cottage, built over a century ago to provide necessities to a working-class population. Many attributes that make it remarkable and a privilege to live in are not feasible or sustainable to deliver today. We should not allow ourselves to become confused by this. Replicating traditional craft practices or allocating large suburban lots in an era of growing land scarcity is not something we need to try and reproduce to make humane dwellings. Architecture can make a meaningful social contribution by thoughtfully arranging space to enhance everyday events and enable civility within urban settings.

We can start by situating openings to receive light and air and admit the presence of nature. That's as simple as making observations about the setting of a building and thinking carefully about where a window is placed in a wall. We can design buildings that dampen sound transmission between adjoining dwellings, are energy efficient and treat the ground plane as a resource, not a potential threat. We can take better care of servicing, ensuring that AC condensers, poo-pipes, and refuse collection aren't immediately adjacent to the lift lobby. We can see communal gardens as more than ornamental. We can design buildings capable of incremental change and adaptation that permit occupants to express their individuality and alter their homes and surroundings to suit their evolving requirements within the framework of a larger building ensemble. If we did that, many more people would have the ability to participate in shaping the city. Our cities would be better able to adapt to new circumstances, and we'd be less reliant on private developers to envisage and deliver our collective futures. These things can all manifest in low-cost, medium-to-high-density buildings supported by parkland and public transport.

These things matter to individuals, but they also resonate within communities, which redounds to our collective benefit. Michael Sorkin's memoir Twenty Minutes in Manhattan is an evocative and insightful account of embodied urbanism in one of the world's most famously dense and highly populated urban environments. For Sorkin, stoops, door thresholds, hallways and stairwells are places of social exchange. The door frame is what we lean on as we lend a phone charger, and the stair is a place to negotiate relationships and swap gossip as people go about their lives. Windows are how we situate our inner lives in the context of a wider world, how the life of the city enters our sanctum. As Sorkin observes:

Such direct transactions are foundational for our politics. Translations of the face-to-face into the door-to-door or into the leaflet passed hand-to-hand in the street are crucial steps in a chain of associations that form a binder for civic life and limn the scale of our community, fixing the dimensions of our collective self-interest, the boundaries of "home." 2

If we thought about buildings in this way, as agents of social and political advancement, we might be inclined to deepen a façade to make it occupiable in places, open a lobby to the outdoors, raise a planter bed to seat height, widen a stair, recess an apartment door to accommodate a pot plant, a door mat and a loitering neighbour. It might only take a few centimetres to create the potential for something important to happen.

Despite how we often simulate architectural practice in universities or critique completed buildings in professional discourse, the architect usually has little control over the work they are offered. They don't typically write the brief, set the budget or conjure the ideal site from a mysterious, hidden orifice. Architectural commissions come unexpectedly, with largely fixed parameters and limited scope for negotiation. Those conditions are not always as ideal as we might wish.

Having a good idea or honourable intentions is only part of the challenge. To turn housing into homes, we need to be persuasive. I know of one prominent practitioner who has joked that his principal skill as an architect is to get his client to double their budget before he's put pen to paper. That kind of talent can also be put to many, more worthy, uses.

Persuasion should begin with compassion and listening. It should also include acknowledging stakeholders who do not have a seat at the table and advocating on their behalf. For a profession allied to and infused with privilege, that's a significant challenge requiring effort. Most practice directors, like me, are incredibly fortunate in both the accident of their birth and their life circumstances. Our client base and social circles typically include people with money, power, and education exceeding the average. Engaging directly with stakeholders, participating in the broader community and staying abreast of public discourse concerning social and economic justice seem like sensible responses. Likewise, talking to your client about the commission quickly reveals where stipulations of the brief are founded on scant evidence or demands are arrived at via untested assumptions. I know from experience that the client and the architect can be vulnerable to such oversights.

A healthy degree of uncertainty is an asset for an architect, not a weakness. Architects tend to know a little about many things. We are generalists coordinating the specialised knowledge of the many experts required to deliver a modern building. Under the right circumstances, we can learn from all of them.

Ultimately, the life of a building is enacted by occupants, not architects, and civility consists of everyday gestures, like kind words, not cladding systems. Architecture can prohibit or encourage certain activities, modifying how and when people encounter one another, how they feel about their environment, and how their environment reflects on them and their prospects in life. However, it takes a lifetime of careful study and observation to demystify the intricate reciprocities between buildings and people. Rather than be deterred or intimidated by that prospect, we should embrace it. Life is fascinating, constantly surprising and inspiring.

When we speak about 'housing' or 'good urban design,' we should base our understanding on people, their dreams and aspirations. Amid a housing crisis that compels us to shift our focus to encompass the magnitude of the challenge, we must avoid losing sight of the salient details, including those who will spend their lives in the spaces created. We cannot afford to rehouse generations of Australians whose hastily constructed neighbourhoods fall into decline because, in our urgency to alleviate a housing crisis, we forget that we are housing humans.

1 For those interested in some insightful observations on this front, see Matt Grudnoff’s recent Guardian article: For housing to be affordable, prices must go down, not up. Here’s how it could happen (8 May 2023). To summarise, stop incentivising investors, invest heavily in public housing, and provide rent assistance now. Also, see Max Chandler-Mather’s recent parliamentary response to the 2023 federal budget.

2 Sorkin, M. (2009). Twenty minutes in Manhattan. London, Reaktion Books Ltd.

2 Sorkin, M. (2009). Twenty minutes in Manhattan. London, Reaktion Books Ltd.