Short Stories from Suburbia

29 September 2016

Masters Studio 2011–2012

The University of Queensland

Words by Aaron Peters

29 September 2016

Masters Studio 2011–2012

The University of Queensland

Words by Aaron Peters

In 2011 and 2012, we were invited to lead a research studio for Masters Students at the University of Queensland. Students were asked to measure and record a single house, its suburban lot, its occupants and their occupation through the mediums of drawing, interviews and photography.

In our time in practice we’ve measured and drawn hundreds of buildings and collected countless stories detailing their occupation. The studio, we hoped, might clarify why we should value this practice of recording and observing.

The following are reflections on the conversations and materials produced in the course of the two research studios.

In our time in practice we’ve measured and drawn hundreds of buildings and collected countless stories detailing their occupation. The studio, we hoped, might clarify why we should value this practice of recording and observing.

The following are reflections on the conversations and materials produced in the course of the two research studios.

Valuing the Everyday

We found ourselves discussing the commonplace. Minor details: crumbling concrete paths, hill hoists, flame trees, lattice screens, door knobs, picture rails, the texture and composition of a vintage lawn. In architecture, scale does not appear to be a barrier to significance. There is an unhurried intimacy in our relationship to the everyday artefact, an intimacy that elicits enduring affection.

As Aldo Rossi observed, a physical artefact can act as a ‘receptacle for collective memory’ that acquires and stores the echoes of the past like a living patina. The commonplace fabric that we identified could be thought of as a network of receptacles experienced contiguously by generations of Brisbanites, an urban fabric that connects and reminds us of our shared provenance.

We contemplated the utility of this observation to the architectural profession and concluded that, if we wish to make connections with those who come into contact with our buildings, we would do this by exploiting the cultural cache embedded in the landscape of the city. Re-valuing the prosaic and the everyday encourages us to see our cultural artefacts as a resource worth preserving.

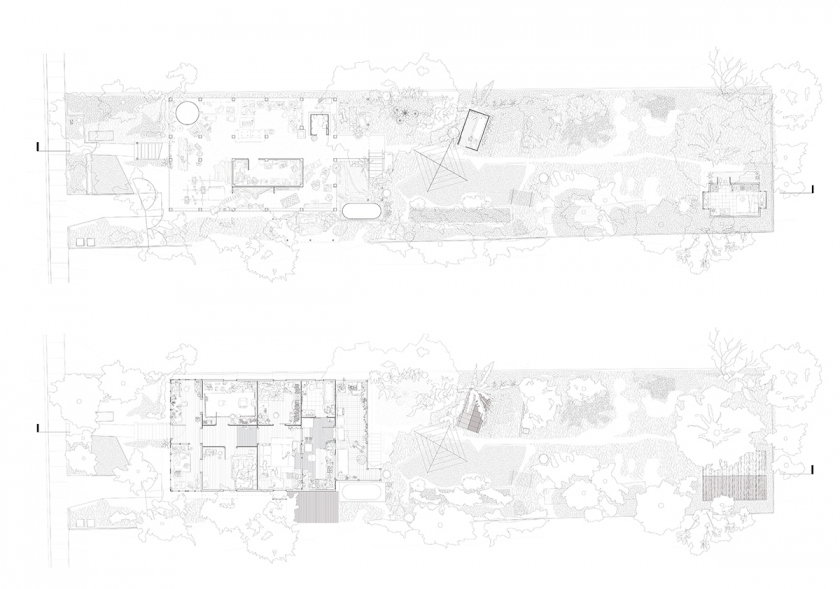

Image: Jonathan Palmer, Alexander Robertson, Siu Man Chan, Tian Sheng

Middle Street House

DIY

A spirit of thrift and ingenuity permeates the built fabric of Brisbane. The contemporary image of the ’Queenslander’ (the timber vernacular house model that dominated the pre and post-war decades in the region) now incorporates the residue of ‘do it yourself’ alterations practised upon it by generations of occupants. In our regular tutorials, we reflected on common DIY practices. Enclosure of the original verandahs is one such activity that has become commonplace throughout Brisbane, creating a distinct room type - the ‘sleepout’- that now characterises the city as much as the iconic Queensland verandah that it habitually supplants.

The DIY artefacts of the garden often reveal unique sensibilities of the residents. Surveying backyards we found paved edging tracing the profile of once verdant garden beds, now resembling obscure glyphs of some forgotten rite; concrete paths jutting out into the lawn to formalise familiar routes between back stairs and the clothes line, furnace or compost heap or the parallel markings of concrete car tracks laid in small articulated slabs, each portion corresponding to the volume of concrete that could be produced by hand on a hot summer afternoon. We reflected on the tactility of these elements, how the concrete aggregate might include fragments of sea shells pilfered with a load of sand by some parsimonious grandfather (e.g. my own).

We discussed how these elements might speak of the circumstance in which they were constructed, of what material might have been to hand or fallen off the back of a truck. How the construction logic might transgress the established norms of conventional practice with results ranging from the inspired to the unintelligible.

Gardens

As part of our research studio we were fortunate to have the guidance of Greg Bamford, a former Lecturer at UQ’s School Of Architecture. Greg’s writings on ‘Garden Oriented Development’ reflect on the utility of private open space. Greg observed that the backyard is a setting for experimentation, cultivation, production and social activity. In urban design terms, the garden permits lightweight timber buildings to open themselves to the breezes, to engage the outdoors. It also allows a child the freedom to explore the world free from direct adult supervision, an adolescent to pull apart a car engine or a family to grow their own vegetables and keep a couple of chooks.

Sharing Greg’s work with the students and listening to his lectures encouraged us to recognise that the sheer volume of open space that Brisbane possesses is remarkable for a city of it size. And, while many see densifying Brisbane as a prerequisite for creating a more sustainable city, we ought to pause and consider the implications of these practices. It also reminded us that there is a symbiosis between the Brisbane house and its garden that underpins what many people have come to see as a ‘Queensland’ lifestyle.

Image: Ami Nakayama

Student Photo Journal

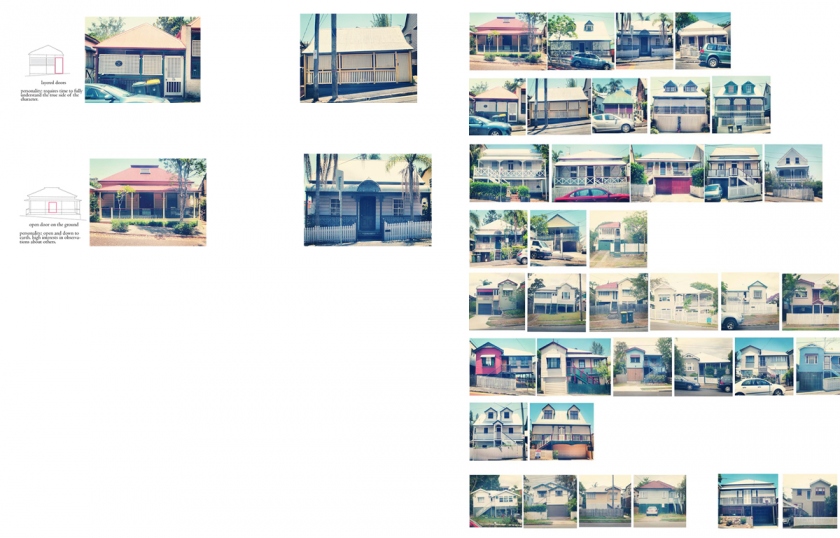

Re-valuing

We spent a good deal of our time as a group talking about the architectural value of the ‘Queenslander’ house and garden. In an age dominated by plasterboard interiors, slab-on-ground construction and shrinking private outdoor space, the experience of a building composed almost entirely of timber board, set in a garden, is extraordinary. To live in a building with single skin walls, tongued and grooved floors, corrugated metal roof sheeting and ‘V’ jointed board lined ceilings that place the soles of your feet a mere nineteen millimetres away from the elements and feuding nocturnal wildlife is a remarkable experience.

As architects, working with these buildings for many years has taught us that the creaking frame of a century-old timber house (with no insulation) can be a challenge. However, the expense of constructing a house like one giant piece of furniture is an almost unimaginable luxury in the present construction climate. These buildings are, generally, beautifully built. The timber is painted to assist in its preservation; ‘Queenslanders’ are not left to rot romantically in the fields like a shed. The utilitarian cottages, even those that did not permit decorative flourishes, have a strikingly modern austerity about them, a rational beauty that merits authentic preservation.

The work of our students, collecting surveys of suburban fabric around the inner city, confirmed that a complex relationship has often existed between the Brisbane house and its custodians. It is common to find timber buildings that were given ill-fitting masonry facades, rendered over or painted and notched to resemble brick coursing. Many homeowners have responded to the utilitarian styling of their worker’s cottages by adding faux wrought iron balustrades, decorative verandah brackets and ornate cornices to ‘elevate’ their abode. More recently, many Queenslanders have been raised to implausible heights, built underneath, had their front stairs lopped off and forced to accommodate grossly over-scaled extensions at the rear that diminish access to private open space and gardens.

Against this backdrop of physical transformation fuelled by rising economic prosperity, we found ourselves searching for distinctive suburban Brisbane narratives. Our students’ collections reveal another Queenslander, one of refinement and dignity with a distinct language of beautiful construction details that could be sympathetically reinterpreted in a contemporary setting. Our study also suggest that open space is worth prizing as highly as buildings themselves.

Finally, we were reminded of the potency of the prosaic, the beauty of the everyday and the capacity of this fabric to enrich our building practices.

Image: Scott Moore, Callum Prasser, Henry Coates, James Baker

Banks Street House

2011

Contributors

Greg Bamford

Nick Skepper

Zuzana Kovar

Angela Hirst

Mathew Aitchison

Michael Dickson

Contributors

Greg Bamford

Nick Skepper

Zuzana Kovar

Angela Hirst

Mathew Aitchison

Michael Dickson

2011

Students

Gemma Baxter

Sandy Cavill

Sui Man Chan

David Churcher

Paulo Frigenti

Tzu-Yuan Lin

Jonathan Palmer

Alexander Robertson

Larissa Searle

Tian Sheng

Students

Gemma Baxter

Sandy Cavill

Sui Man Chan

David Churcher

Paulo Frigenti

Tzu-Yuan Lin

Jonathan Palmer

Alexander Robertson

Larissa Searle

Tian Sheng

2012

Contributors

Greg Bamford

Doug Neale

James Davidson

Carol Doyle

Krista Berga

Contributors

Greg Bamford

Doug Neale

James Davidson

Carol Doyle

Krista Berga

2012

Students

James Baker

Elizabeth Bennett

Natasha Chee

Greg Clarke

Henry Coates

Ziggy Jarzab

Tess Martin

Ami Nakayama

Callum Prasser

Ben Sheehan

Shane Willmett

Students

James Baker

Elizabeth Bennett

Natasha Chee

Greg Clarke

Henry Coates

Ziggy Jarzab

Tess Martin

Ami Nakayama

Callum Prasser

Ben Sheehan

Shane Willmett