To Make and to Mend

August 2019

In The Material City 2020: ed. Ron Ringer

Words by Aaron Peters

August 2019

In The Material City 2020: ed. Ron Ringer

Words by Aaron Peters

My grandfather was a maker of things, a remnant of a time when something broken would be mended, when something required might be fabricated rather than purchased. When I would visit, he would invariably have some small task underway. I watched him work, using a hand saw to slice hardwood with the ease of a power saw, or rummaging through a collection of building materials stowed in the rafters, and I became aware of a particular design sensibility at play. His creations were lithe, economical in material and manpower, but always neat, stoutly made.

Two decades of study and practice later, I am conscious that my own design sensibilities are irredeemably clouded by professional training. Perhaps this is why I delight in the prosaic, the Do It Yourself. These creations are free to draw inspiration from any quarter, to transgress boundaries of good taste and propriety without the self-awareness that habitually clings to professional aesthetes and designers.

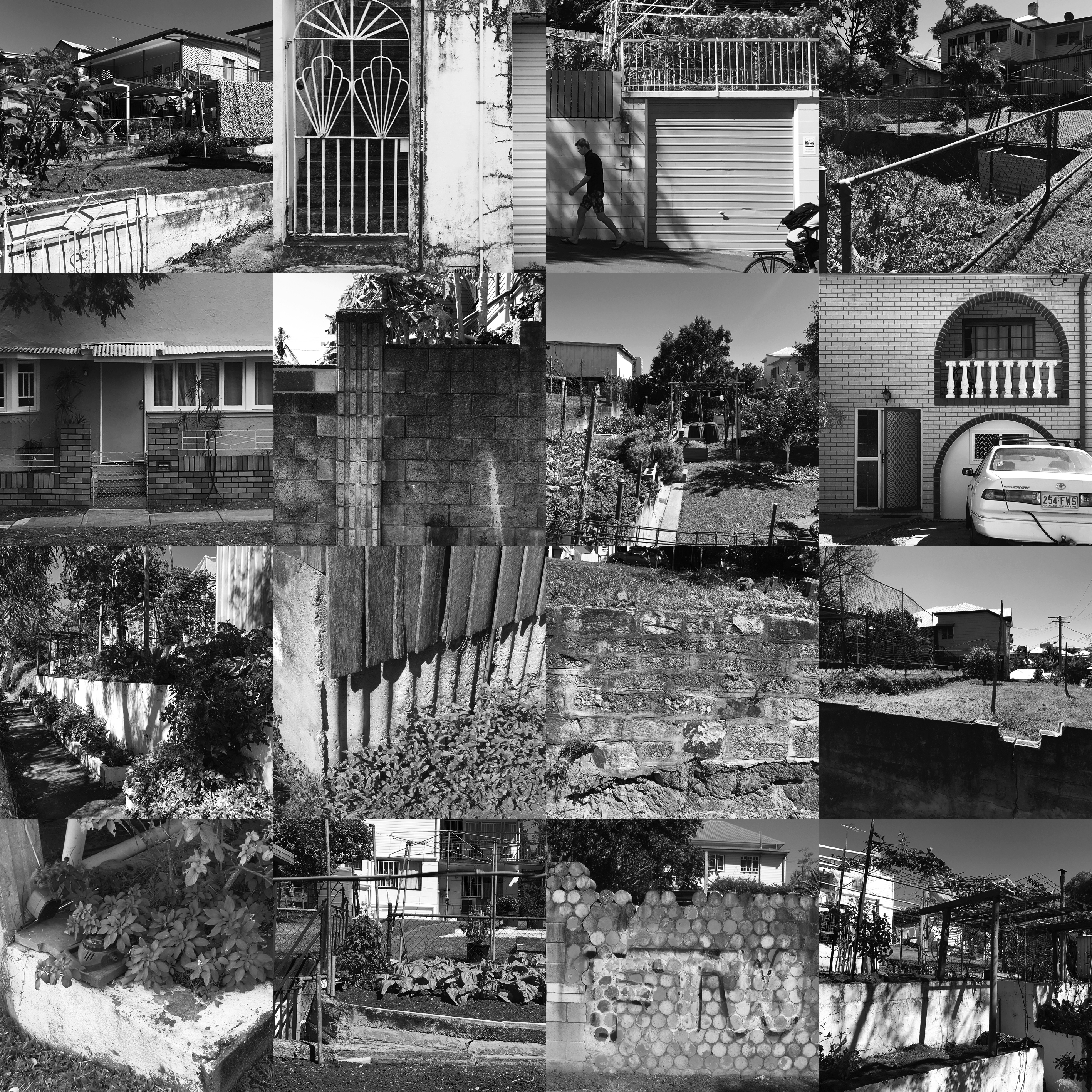

Brisbane’s inner city suburbs of

South Brisbane, West End and Highgate Hill abound with remnants of a vibrant

DIY culture: verdant productive gardens; ancillary backyard structures of

concrete and masonry; ornate metalwork; faux brick cladding over timber

weatherboards and liberal use of brick arches.

We were approached by a young family looking to return to these parts (one of whom had lived in the area growing up and both having attended the local high school). The house they had purchased was likely to have been the home of George Wilson, the first white settler and purported originator of the name: Highgate Hill. Little, however, remained of the ‘plaster-lined’ original house, with wrap-around verandah, cedar stair case, dual attic rooms and shingle roof. All were stripped out over time, and a mid-century renovation went so far as to remake the original transverse gabled roof into a pyramidal form and replace the tall double hung windows with horizontal format casements. For this house, there would be no going back, but there was a possible trajectory.

We were approached by a young family looking to return to these parts (one of whom had lived in the area growing up and both having attended the local high school). The house they had purchased was likely to have been the home of George Wilson, the first white settler and purported originator of the name: Highgate Hill. Little, however, remained of the ‘plaster-lined’ original house, with wrap-around verandah, cedar stair case, dual attic rooms and shingle roof. All were stripped out over time, and a mid-century renovation went so far as to remake the original transverse gabled roof into a pyramidal form and replace the tall double hung windows with horizontal format casements. For this house, there would be no going back, but there was a possible trajectory.

Rather than try and reclaim the

original building that had been lost, we drew upon the traditions of the

surrounding suburb. The unifying feature of the new work is an encompassing garden

wall of painted brick. Struck flush and loosely laid, the bricks fold to slice

the sunlight into hard shadows. Arched openings with brick screen allow the

wall to open to the hilltop park behind. Openings permit glimpses into the two

courtyard gardens. In time, foliage will reach up and enwrap the masonry, fill

out the courtyards and spill over to the street edge. Fine steel gates and

screening, constructed by our client’s father, a metal worker of Greek

extraction, ornament the building.

Of course, this isn’t an authentic DIY; it’s homage – an attempt to assimilate this well appointed contemporary house into a local building tradition. It’s also an attempt to exploit a resource, to draw upon a wealth of embedded collective memory and cultural cache that has built up in this place over time.

DIY often belongs to the everyday artefact, the parts of a building most frequently handled, the most heavily invested with the markings and memories of making. They mean something to someone because they solved a particular problem or satisfied a particular longing that existed in a particular place at a particular time. As design professionals, it isn’t possible to replicate this authentic form of production, but studying it can serve as a reminder of the emotional and experiential potency of the vernacular.

Of course, this isn’t an authentic DIY; it’s homage – an attempt to assimilate this well appointed contemporary house into a local building tradition. It’s also an attempt to exploit a resource, to draw upon a wealth of embedded collective memory and cultural cache that has built up in this place over time.

DIY often belongs to the everyday artefact, the parts of a building most frequently handled, the most heavily invested with the markings and memories of making. They mean something to someone because they solved a particular problem or satisfied a particular longing that existed in a particular place at a particular time. As design professionals, it isn’t possible to replicate this authentic form of production, but studying it can serve as a reminder of the emotional and experiential potency of the vernacular.